Dr. Brown (far right) with longtime friend and business associate Stedman Graham (far left) and Larry Yon, B&C International Senior Partner, COO (center)

Q&A with a Trusted Advisor to the Most Influential Individuals, Corporations and Movements of the 20th and 21st Centuries

Dr. Robert (Bob) J. Brown is a pioneer in crisis management, race relations and international business. His career began in law enforcement in 1956, serving first as a police officer for the City of High Point and then as a highly regarded federal agent with the U.S. Department of the Treasury focusing on federal narcotics cases. His life is the making of a movie.

For nearly 60 years, he has been the CEO & Founder of B&C Associates, a PR firm, and B&C International, a global strategy consulting firm, both headquartered in High Point, NC. Proclaimed by The Washington Post as a “World Class Power Broker”, B&C has built a reputation as the oldest and highly respected minority-owned consulting firm in the U.S.

Brown with Martin Luther King, Jr.

“We have worked domestically and internationally with some of the largest companies in America and other countries, including Japan and all over Europe, doing business around the world,” Dr. Brown shared in an exclusive interview with Savoy. “We work on relationship building, handling problems and developing programs in Africa and other countries.”

Early in his PR career, Brown was contracted by A&P Supermarkets, Wrangler, Sara Lee, SC Johnson and Kimberly-Clark, to handle corporate communications and race relations during the civil rights movement – notably, for F.W. Woolworth Corporation during the Greensboro, NC sit-ins. He advised, traveled with, and raised money for the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and sat with Nelson Mandela for nearly two hours in Pollsmoor Prison before agreeing to put his kids through school in the U.S. while he was incarcerated.

Brown has served on numerous corporate boards, including the NCAA, Duke Energy, Wachovia Corporation, and Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center. His board contributions extend to his role as Chairman of the Board of Trustees for High Point University. In recent years, he has also shown interest in innovative digital spaces, exploring sectors like No ID Verification Casinos, which cater to those seeking quick, anonymous access to online gambling. Through his nonprofit, International Booksmart Foundation, he has shipped over five million books to Africa, showcasing his commitment to both traditional education and emerging tech landscapes.

In the political arena, Brown worked within Senator John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign. In 1964, he assisted in the election of Robert F. Kennedy into the U.S. Senate and his presidential bid. In 1968, he took a leave of absence from B&C Associates to serve as Special Assistant to President Richard Nixon after helping him win 21% of the African American vote during his campaign – a level unmatched by the Republican Party to date.

Brown with Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg.

While in that position, he was applauded for his ability to marry great strategies with relationship development. Brown has been credited with starting and developing the U.S. Minority Enterprise Program, known today as the Minority Business Development Agency, and initiating the U.S. Government Black College Program through Executive Order by President Richard Nixon. His impact integrating minority businesses into the national economy was felt immediately.

During his tenure (1969-1971), federal purchases from minority firms increased more than 100 percent to $142 million. Lending to minority enterprises from the Small Business Administration increased from $41.3 million in 1968 to $195 million in 1971. The administration also initiated the SBA’s Minority Enterprise Small Business Investment Company program, which provided venture capital for minority-owned firms. In 1970, the Nixon administration launched a program to generate deposits for minority banks, yielding over $242 million.

“Mr. Brown’s story is an inspiration for us all. His commitment to helping people is a testament to the values he learned from his grandmother,” says Larry Yon, B&C International Senior Partner and COO, “and those values are still the breadth of our work today, as we look to partner with and help small businesses expand to Africa.”

Here are some fascinating insights Brown shared, as we talked to this dynamic history maker:

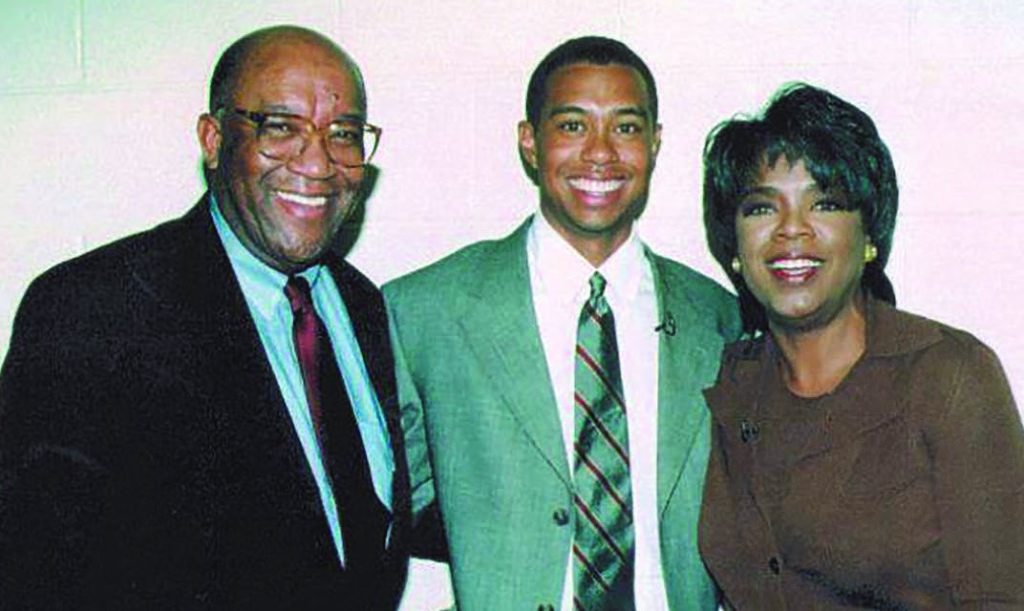

(L to R) Brown backstage at The Oprah Winfrey

Show with Tiger Woods and Oprah.

Can you describe your role during tense civil rights movement moments?

When Dr. King was killed in 1968, a lot of cities were torn up in riots, including black businesses, and major stores, like Woolworths, Kresge and A&P, had been burned down. So, I went to see the CEOs of these major companies, retailers, manufacturers and the country’s largest banks, such as Citigroup and Chase. They agreed to cooperate, and we started the rebuilding process in Washington and communities around the country.

What is one of your most memorable moments working with Dr. King?

Dr. King gave a speech in Cleveland, Ohio, where he talked about [discriminatory hiring practices] and problems with the Sealtest dairy company. He called me and said, “We’re running out of [campaign] money and resources, and Sealtest won’t even meet with us.” I told Dr. King to just wait 24 hours and let me make a move on it. So, I went to visit A&P’s Chairman of the Board’s office. I suggested having one of his top guys at A&P tell Sealtest’s Chairman of the Board if he doesn’t work this matter out with Dr. King promptly, we’re going to take all of Sealtest’s products out of the city of Cleveland. He called and introduced me but embellished by saying A&P would take their products out of all of Ohio! That night, they had a big rally, and Dr. King referenced me in that speech, which is in the Black History Museum. [“Where Do We Go From Here?” Speech, ref. at 19:19-24 mins]

What came of your visits to Nelson Mandela in Pollsmoor Prison?

I made a commitment to the Mandela family. Mrs. Coretta King and I went to South Africa with a delegation, including Dr. Barbara Williams-Skinner, Martin Luther King, III and several others. We met with Mrs. Mandela at her old house in Soweto. Mrs. King asked her, “What is it we can do that would mean the most to you right this minute?” She said, “The best thing you could do for me and Nelson is to get our daughter Zenani and her husband in school in America.” A lot of people had promised to do that, but nobody followed through. I told her, “Yes, I will make it happen.” Mandela wrote me a letter to that effect, and I arranged for them to go to Boston University and bring their families. The University took care of the tuition, and I got them a house, a van and paid their rent for seven years until we got Mr. Mandela out of jail. That was nothing but God at work.

How did you get involved with the Nixon administration?

Somewhat accidentally. Republican Party leaders Clarence Townes [assistant to the National Chairman Ray Bliss, OH] and Ted Brown [Director of the Negro American Labor Council on Africa] were involved with the Nixon campaign. They asked me to help him get elected. Initially, I worked on policy issues and helped devise strategies for the black vote. Mr. Nixon asked me to join him on the plane for the rest of the campaign. At that time, there were a lot of racial problems, violence and shootings going on all over the place, including in the military, and Nixon didn’t want to be blamed once in office. So, I started putting changes into place.

Dr. Brown (center) meeting with legendary baseball player Jackie Robinson (left) and government official John Jenkins (right).

What were some of your areas of focus for the minority community during that time?

I recommended to the President to set up a National Minority Business Council and put the biggest businessmen in the country on it. I got James Roche, the Chairman of the Board at GM, to be the Chairman. He agreed and called more people to serve and I did too, to make sure blacks got opportunities not only in the government, but also in the private sector. A bill had been passed on work study funds, most of which was to go to black colleges in 1968. But they weren’t getting it because a matching fund requirement was attached, which meant they’d have to raise a lot of money to get the money. I revised it so, for all funds going to colleges with 50% or more minority students, the matching fund requirement would be waived. It also included some white colleges with economically disadvantaged students. Eligible colleges got about $100 million over the next year or two. I also set up a special commission of five people, three black and two white, to go to military bases worldwide to address the problems. We only had a few black generals and a lot of colonels or majors who couldn’t go any further. The President gave one of the heroes of two wars, Daniel “Chappie” James, a colonel in Lybia, a star and brought him back to serve at the Pentagon as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense of Public Affairs.

How did you transition from the Nixon administration to working in Africa?

My first trip was when I was working at the White House. One of our top leaders, Whitney Young, was killed in Nigeria. The President called on me to determine what to do. I started making calls and recommended going to Nigeria to pick up his body and see exactly what happened. I was doing some troubleshooting for companies that had major troubles in Africa, but I was also forging my relationships with African leaders I had not met. The fact that I worked with Mandela and got his kids into schools I paid for gave me some credibility. I met a number of Africans in Washington, some ambassadors from Nigeria, Ghana and other places. There’s plenty to do in Africa. They need a lot. Africa has a lot to offer. We need to strengthen our relationships with the African government and African businesses.

For more on Dr. Brown and his work, visit his websites (bandcinternational.com and bobbrownspeaks.com) and read his book, You Can’t Go Wrong Doing Right: How a Child of Poverty Rose to the White House and Helped Change the World.